Beneath the Surface: Mapping the Scars of Colonial Power

Louise Deininger

September 10 - October 18 2024

The exhibition Beneath the Surface: Mapping the Scars of Colonial Power offers a nuanced exploration of the lasting impacts of colonialism on African societies, identities, and cultures.

Louise Deininger seeks to unravel the complexities of post-colonial trauma, resilience, and the ongoing struggle for cultural reclamation, with focus on the East African block based on her upbringing and her experiences in Uganda and Kenya. This exhibition draws on the intellectual foundations laid by some of the most significant African theorists, including Frantz Fanon, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, Kwame Nkrumah, Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, and Achille Mbembe, among others. Their insights into the psychological, cultural, and economic ramifications of colonialism provide a critical framework for understanding the themes of Deininger’s work.

-

Colonialism in Africa was not merely an economic or political enterprise; it was a comprehensive system designed to reshape African societies at their core. European colonial powers imposed their languages, religions, and political structures on African people, often with devastating effects. This process of cultural and political domination, as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o argues in his seminal work Decolonising the Mind, amounted to a "cultural bomb" aimed at erasing African cultures and replacing them with the values and ideologies of the colonizers. Ngũgĩ’s concept of the "cultural bomb" is particularly relevant to understanding the deep psychological scars that colonialism has left on African societies. He writes, “The effect of a cultural bomb is to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves”. These scars manifest not only in the loss of language and cultural practices but also in the internalized perceptions of inferiority that many Africans continue to grapple with.

Frantz Fanon, another towering figure in post-colonial thought, delves deeply into the psychological effects of colonialism in his works Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth. He describes how colonialism instills a sense of inferiority in the colonized, leading to a "colonized mind" that internalizes the dehumanizing views of the colonizer. “The colonized is elevated above his jungle status in proportion to his adoption of the mother country’s cultural standards”. This psychological condition, according to Fanon, is one of the most insidious legacies of colonialism, as it perpetuates a cycle of self-hatred and dependency even after the end of direct colonial rule.

Colonialism disrupted a rich tapestry of pre-colonial African civilizations, which had their own sophisticated systems of governance, culture, and trade. Prior to European colonization, Africa was home to thriving empires such as the Mali, Songhai, and Great Zimbabwe, which were centers of learning, architecture, art and commerce. Timbuktu, for instance, was renowned for its libraries and Islamic scholarship, attracting scholars from across the world. The Kingdom of Kongo and the Ashanti Empire had highly organized political systems and engaged in extensive regional and global trade. These civilizations were self-sustaining, with rich traditions in art, science, and law, debunking the colonial myth of Africa as an uncivilized land. The imposition of European rule, with its dismissal of these achievements, not only dismantled these structures but also imposed an external culture and economy that disconnected Africans from their heritage. The legacy of this cultural erasure is still felt today, as post-colonial societies struggle to rebuild and reclaim the grandeur of their pre-colonial histories.

The exhibition’s focus on the psychological and cultural scars left by colonialism resonates strongly with Fanon’s analysis, as it highlights the ongoing struggle for mental and cultural liberation in post-colonial Africa.

-

Art has always been a powerful tool for resistance and healing in the face of oppression. In the context of post-colonial Africa, art serves as a means of expressing the pain and trauma inflicted by colonialism, while also offering a path toward reclaiming and celebrating African identity. Louise Deininger’s work is a prime example of how art can function as both a reflection of and a response to the enduring impacts of colonialism. Her use of materials such as elephant dung, cowry shells, Kanga cloth, Ugandan bark cloth and Ghanaian tree bark is deeply symbolic, connecting her art to the land, culture, and history of Africa.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s call for the decolonization of African minds through the revival of African languages and cultural practices finds a visual counterpart in Deininger’s art. By using materials that are inherently African, Deininger is participating in the larger project of cultural reclamation that Ngũgĩ advocates. Her work challenges the legacy of cultural erasure imposed by colonialism and underscores the importance of reconnecting with African traditions as a form of resistance. As Ngũgĩ states, “Language, any language, has a dual character: it is both a means of communication and a carrier of culture”. Deininger’s work, through its use of culturally resonant materials, embodies this duality, communicating both a critique of colonialism and a celebration of African culture.

-

While the formal period of colonialism may have ended, its scars remain deeply embedded in African societies through the mechanisms of neo-colonialism. Kwame Nkrumah, one of the foremost theorists of neo-colonialism, articulated how former colonial powers and other global forces continue to exert control over African nations through economic and political means, even after these nations have achieved political independence. In his Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, Nkrumah argues that neo-colonialism is more insidious than direct colonial rule because it maintains the illusion of independence while perpetuating dependency and exploitation: “The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside”.

Louise Deininger conceptualizes her work as a direct critique of these ongoing neo-colonial dynamics. In recent years, Deininger’s birth country, Uganda, has seen significant political protest, driven by the countries’ youth, who are frustrated by political repression, economic hardship and the long-standing rule of President Yoweri Museveni (since 1986). This authoritarian rule is deeply intertwined with colonial legacy: the roots of contemporary political instability can be traced back to the era when European powers drew arbitrary borders, grouped together diverse ethnic communities, and established systems of governance that favored centralized control. The British colonial strategy of indirect rule fostered ethnic divisions, favoring certain groups over others, which created tensions that continued to plague Uganda after independence. Post-colonial Uganda, like many African nations, inherited not only these colonial borders but also the centralized systems of governance and military force established during colonial rule. Museveni’s regime, which began with promises of liberation and democracy, eventually adopted similar authoritarian tactics to maintain power, much like the colonial administrations that relied on military force and suppression to control the population. His regime has been characterized by the suppression of opposition, human rights abuses, and the manipulation of constitutional processes to expand his rule – practices that echo the colonial methods of governance. Museveni’s regime has responded to protests with violent crackdowns, and ever since 2020, when the leader of the opposition, Bobi Wine, was arrested, many young Ugandans were killed by security forces using live ammunition, tear gas and other forms of repression. Human rights organizations have condemned the government’s oppressive tactics, which include arbitrary arrests, disappearances and torture of protesters. The continuity between colonial and post-colonial governance is evident in how many African leaders have used the structures left behind by colonial powers to enrich their authority. Colonialism not only disrupted African societies, but also left a legacy of governance that emphasized coercion and militarism. Museveni’s prolonged rule can therefore be seen as part of a broader pattern in post-colonial African states where leaders, in response to internal pressures and legacies of instability, replicate the same oppressive tactics once used by colonial powers to maintain control. These protests reflect deep-stated anger over authoritarian rule, corruption and lack of opportunities. Deininger, having witnessed the grief and heartbreak of mothers who see their children off when joining a protest, not knowing whether they will survive or not, reflects these desperate and infuriating state of affairs in her art works. Her Kanga installation addresses the red line crossed by an oppressive neo-colonial ruling system. Her work not only critiques the legacies of colonialism but also affirms the strength and resilience of contemporary African youth striving for self-determination in the face of ongoing attempts to dominate and control them.

-

The history of colonialism in Africa is a history of violence, exploitation, and cultural erasure. However, it is also a history of resistance, resilience, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination. Historians like Walter Rodney, in his influential work How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, have documented the economic impacts of colonialism on the African continent, showing how colonial powers systematically underdeveloped Africa for their own benefit. Rodney argues, “African economies were integrated into the very structure of the capitalist system that was being imposed upon the world by Europe”. Rodney’s analysis provides a critical economic context for understanding the material conditions that Deininger’s art addresses.

Rodney’s work also intersects with the sociological perspectives offered by thinkers like Ali Mazrui and Thandika Mkandawire, who have explored the cultural and social dimensions of post-colonial Africa. Mazrui’s concept of the "triple heritage" in Africa—comprising indigenous, Islamic, and Western influences—offers a framework for understanding the complex cultural dynamics at play in Deininger’s art. Her work reflects the multiple layers of African identity that have been shaped by these diverse influences, while also asserting the primacy of indigenous African cultures.

This interplay of heritages is embodied in Deininger’s works The Portal and Shadow III. Both objects are sculptural pieces made from elephant dung, clay, and wooden Catholic rosaries, incorporating traditional African materials with elements of Western religious iconography.

The Portal resembles a spherical or circular form with wooden rosary beads draped around it, suggesting the intertwining of traditional African materials with symbols of Western religious devotion. The object is a subtle interplay between the rough texture of clay and elephant dung with the polished surface of wooden beads of the Catholic rosary, emphasizing the hybrid result at the confluence of spiritual belief systems.

Shadow III. is a wall-mounted piece. It features a circular form made of elephant dung, decorated with cowry shells arranged around a mirrored central space, surrounded by a wooden rosary chain. The rosary extends downward, its beads resembling traditional African prayer or healing necklaces but clearly identified as Catholic.

The use of elephant dung and clay taps into traditional African art and spirituality, particularly the close relationship between African societies and the natural environment. Elephant dung is not only a symbol of fertility and life cycles but also a material that connects the work to the earth and ancestral spirits. In many African traditions, natural materials like clay and organic matter are used to create ritual objects and sculptures with spiritual significance. The use of cowry shells reinforces this connection to African cultural symbols of wealth, fertility, and protection.

The Catholic rosaries represent the Western, colonial influence on African societies, particularly the introduction of Christianity through European missionaries. Catholicism has a complicated history in Africa, often associated with violence and the imposition of Western values over indigenous practices. By integrating the rosary beads with elephant dung, Deininger comments on the juxtaposition and coexistence of African spirituality and Christian religious practices in post-colonial African identity. The proportionally oversized Catholic rosaries entwined around the African materials symbolize the imposition of Christianity, but also how these two traditions have been forced to coexist. Deininger’s work suggests that while these traditions may coexist, there is a constant negotiation and transformation of identity. By placing such contrasting materials together, she challenges the viewer to consider how Africa’s indigenous heritage has been shaped and reshaped by colonial histories yet remains resilient and vital in its cultural significance. The materials themselves speak to the persistence of African culture, even in the face of imposed Western religious structures.

-

Kanga cloth is a vibrant, colorful fabric that is embedded in the cultural life of East Africa, particularly in countries like Kenya and Tanzania. The origins of Kanga cloth date back to the mid-19th century, when the fabric began to emerge as a distinctive part of Swahili culture. Kanga cloth is typically characterized by its bright colors, intricate patterns, and, most notably, the inclusion of a proverb or saying, known as a "jina," which is printed on the fabric. Originally, Kanga cloth was created from a combination of imported cotton fabrics and traditional designs. The cloth was often worn by women as a wrap or shawl, and it quickly became a symbol of cultural identity and communication among East African women. The motifs and proverbs printed on Kanga cloth are used to convey messages, celebrate occasions, or even subtly express social and political commentary.

Colonial Influence on Kanga Motifs:

The motifs and designs on Kanga cloth have been significantly shaped by the region's colonial history. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, East Africa was under the colonial rule of various European powers, including the British and Germans. This colonial presence influenced the production and aesthetics of Kanga cloth in several ways.

The colonial period saw the introduction of new motifs and patterns on Kanga cloth, influenced by European tastes and the influx of imported fabrics. Some designs began to incorporate elements of Western fashion and iconography, blending them with traditional African patterns. This fusion created a unique visual language that reflected the complex interactions between African and European cultures during the colonial era.

Kanga cloth became a medium for subtle political resistance during the colonial period. The proverbs and sayings printed on Kanga often contained veiled critiques of colonial authorities or expressed hopes for independence. These messages were sometimes encoded in language or symbolism that was understood by local communities but not by colonial officials, making Kanga cloth a powerful tool for resistance and communication.

Under colonial rule, the production of Kanga cloth became increasingly commercialized, with European textile companies producing and exporting the fabric back to East Africa. This commercialization led to the standardization of certain motifs and the introduction of mass-produced designs that were influenced by colonial marketing strategies. Despite this, Kanga cloth remained a vital part of East African culture, with local artisans continuing to innovate and create new designs that reflected the region's cultural and political dynamics.

After independence, Kanga cloth continued to evolve, with new motifs reflecting the changing social, political, and economic realities of East Africa. The proverbs and sayings on Kanga cloth often address contemporary issues such as women's rights, political leadership, and social change, showing how the fabric remains a living document of the region's history and culture.

In Louise Deininger's work, the use of Kanga cloth serves as a reminder of this rich history and the ways in which African cultural practices have been shaped by, and have responded to, colonial influence. The incorporation of Kanga cloth into her art is not just an aesthetic choice but a deliberate engagement with the fabric's role as a medium of communication, resistance, and cultural identity in East Africa.

Generation Z by Louise Deininger wraps the entire room in Kenyan Kanga cloth, creating an immersive environment where every surface—walls, ceiling, and floor—is adorned with vibrant, patterned fabric. The Kangas feature traditional Swahili designs, characterized by intricate geometric patterns in red, black, yellow, and white. Within this colorful setting, two framed paintings hang on the wall, slightly separated from the viewer by a string of red ropes stretched across the space. The rope symbolizes a boundary, referring to a metaphorical "red line" crossed by the government in suppressing youth protests, particularly those against political repression and state violence in Kenya and Uganda.

The atmosphere within the installation is both intimate and overpowering. The familiar texture and patterns of the Kanga cloth are traditionally used for clothing and personal expression in East Africa, but here they become a full-scale environment, transforming the space into a cocoon of memory and cultural history. The red rope creates a visual interruption, serving as a barrier between the viewer and the art on the wall, symbolizing not only physical restriction but also the emotional and political lines that have been crossed.

Louise Deininger’s installation is a powerful meditation on the themes of cultural identity, political resistance, and the repression of youth movements in her home countries of Uganda and Kenya. The Kanga cloth, deeply embedded in the daily lives of East African women, traditionally serves as a medium of communication, with printed proverbs or sayings offering wisdom, social commentary, or political statements. By covering the entire room in Kanga, Deininger transforms a common, personal fabric into a larger political statement, connecting the intimate with the political.

The red rope that runs across the space is symbolic of the government’s violent repression of the youth-led protests in both Uganda and Kenya. It alludes to the limits that have been crossed—both in terms of state violence and the loss of rights. The rope's placement, separating the viewer from the paintings, evokes feelings of restriction and frustration, paralleling the experiences of young activists who have been silenced or suppressed in their efforts to push for change.

Frantz Fanon’s analysis of violence in The Wretched of the Earth provides another lens through which to view this installation. Fanon argues that violence is both a tool of the colonizer and, inevitably, a tool of the oppressed in their struggle for liberation. Deininger’s "red line" evokes this dynamic: the government’s violence is depicted as a transgression, while the installation itself becomes a space for contemplation of resistance. The immersive use of Kanga reflects the idea that culture and resistance are inseparable, while the red rope alludes to the lines that the state has crossed in repressing its citizens.

In this installation, the viewer is not just a passive observer but is placed in the middle of this tension, surrounded by symbols of identity and struggle. The Kanga-clad room creates a protective, yet suffocating environment, representing both the endurance of cultural identity and the pressures exerted by political repression. The red line becomes a stark reminder of the limits of freedom in the current socio-political context, emphasizing the urgency of the youth’s call for change and their resilience in the face of oppression.

-

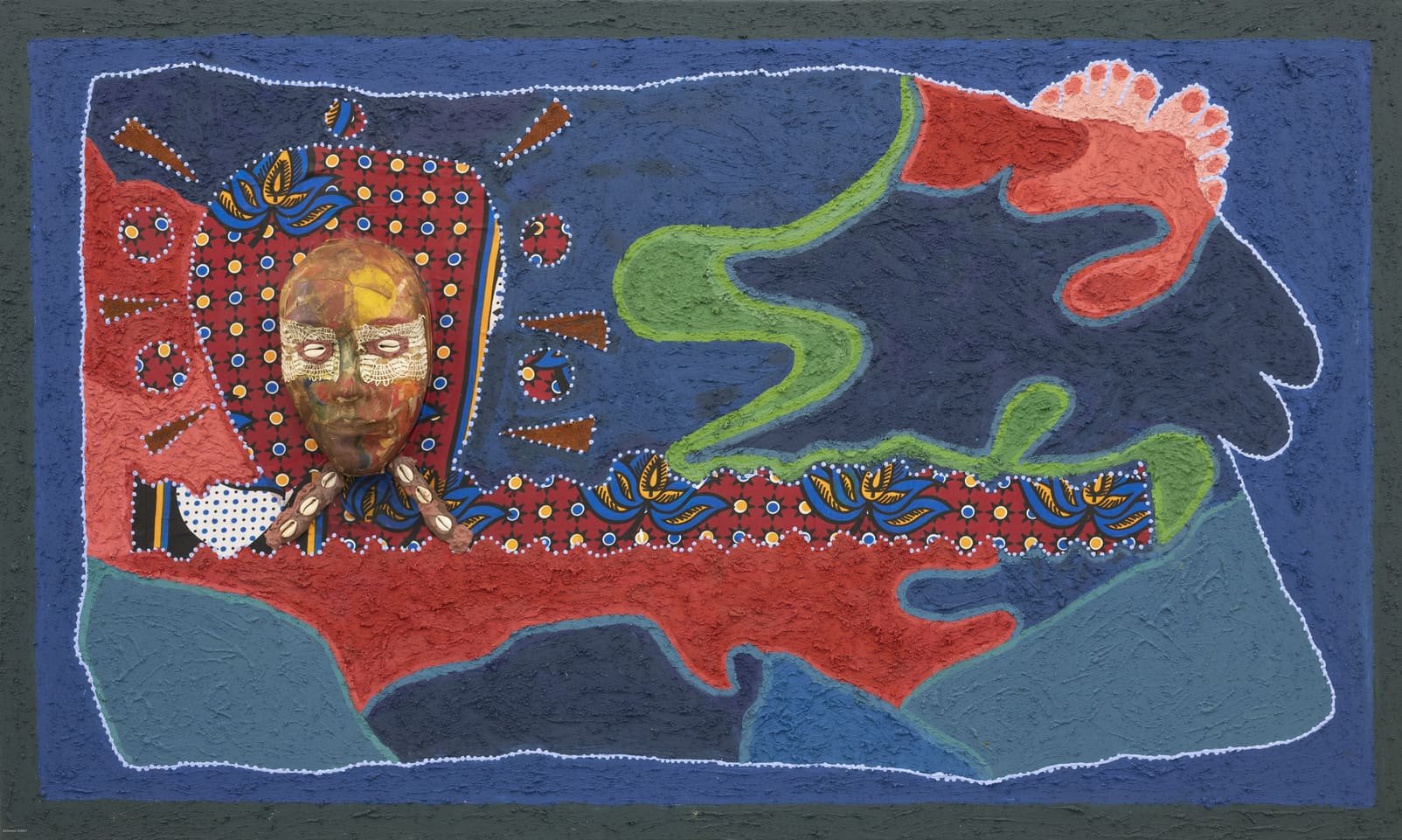

Louise Deininger’s paintings are characterized by a richly textured technique that blends organic materials – such as elephant dung, cowry shells, Ugandan bark cloth, Ghanian tree bark and Kanga cloth – with vibrant acrylic pigments. This combination creates a tactile, layered surface that evokers a sense of depth and earthiness. Her iconography often includes masks, abstract forms and a plethora of symbolic motifs.

Her work Negatives features five mask-like forms set against an earthy background. The masks are varied in color and material, with some three-dimensional and others left as blank silhouettes. They sit atop a horizontal line made of elephant dung and tree bark, while cowry shells and crochet accents create intricate details. The background is divided into red, blue, and earthy brown sections, evoking natural and cultural connections. The masks evoke themes of identity and presence, tapping into the long history of mask-making in African art. Traditionally, masks are used in rituals to represent ancestors, spirits, or collective identity. Here, the blank or hollow masks seem to speak to erasure—perhaps reflecting how African identities were fragmented by colonialism. The use of cowry shells, symbols of wealth and spirituality in many African societies, reinforces the connection to cultural heritage. Deininger’s use of elephant dung brings an additional layer of meaning, emphasizing the organic connection between the land and cultural memory. Elephant dung, in this context, symbolizes continuity and the cycle of life, adding a rich tactile and symbolic dimension to the work.

Similarly, Womb I. and Womb II. feature a large circular, womb-like form dominating the canvas, constructed from red-stained cloth, which was used to clean up another installation. The central form emerges from the base of elephant dung, with swirling patterns in blues and earth tones surrounding it. Cowry shells line the edges, enhancing the symbolism of fertility and creation.

The imagery of the womb is potent in African art, symbolizing fertility, creation, and the nurturing aspects of womanhood. By reusing the red-stained cloth, Deininger imbues the piece with themes of renewal, transformation, and the cyclical nature of life. The cloth is a by-product, reinforcing the idea that creation can arise from destruction, much like how African identities have evolved and regenerated in the face of colonial oppression. The swirling colors and patterns evoke the constant movement of life, growth, and cultural exchange, while the elephant dung grounds the piece in the earth, symbolizing resilience and continuity.

Unity centers on a mask surrounded by vibrant Kanga cloth patterns and flowing abstract shapes. The mask’s eyes are adorned with cowry shells, and the texture of the piece is rich with the integration of natural materials like elephant dung. The flowing colors and shapes seem to suggest movement and connection, while the Kanga cloth—a textile associated with East African identity and communication—provides cultural grounding.

Unity reflects Deininger’s interest in the cultural ties that bind individuals to their heritage. The mask symbolizes ancestral connection, while the cowry shells evoke spiritual protection. The use of Kanga cloth is significant because it traditionally carries Swahili proverbs and social commentary, functioning as both a symbol of cultural identity and a form of communication. This ties into themes of collective identity and resilience, suggesting that despite colonial disruption, cultural unity endures.

Path also features a single mask with cowry shell accents on its eyes and necklace. The mask is set against a richly textured background of abstract shapes and patterns, rendered in red, blue, and green. The mask is framed by intricate crochet work, adding a delicate, feminine touch to the otherwise bold and earthy materials like elephant dung.

The title Path suggests a journey—perhaps a metaphorical or spiritual one. The mask, with its cowry shell eyes, seems to gaze out, serving as a guide or protector along this path. The organic, flowing shapes and earthy materials suggest a connection to the land and the cyclical nature of life, while the crochet details evoke themes of femininity, care, and cultural preservation, often associated with women's roles in many African societies. By combining crochet with rougher materials like elephant dung and bark, Deininger bridges the gap between softness and strength, underscoring the resilience required to navigate the "path" of post-colonial identity.

The presence of cowry shells, historically used as currency and spiritual objects, reinforces the notion of guidance, protection, and value. The "path" suggested by the mask’s forward gaze could symbolize both personal and collective journeys toward healing, decolonization, and reclaiming African identity after colonial disruption.

Louise Deininger’s art presents a powerful dialogue between the historical, cultural, and social realities of post-colonial Africa and broader global themes of identity, reclamation, and resistance. Her use of natural materials such as elephant dung, cowry shells, Kanga cloth, Ugandan bark cloth and Ghanaian tree bark situates her work within both traditional African artistic practices and contemporary post-colonial discourse. In this analysis, we will examine Deininger's techniques, iconography, and subjects, placing her within the broader context of African and Afro-American artists who have similarly explored these themes.

Her particular use of materiality connects Deininger to artists such as Chris Ofili, known for his provocative use of elephant dung in works such as The Holy Virgin Mary (1996). Ofili challenged Western perceptions of "purity" in art by incorporating elephant dung as a material representing both the sacred and the profane. Like Ofili, Deininger employs elephant dung not simply as a medium but as a symbol of African culture, history, and connection to the land. The material’s presence in both artists' works invites discourse on the commodification of African culture and the tension between Western and African perspectives.

Similarly to El Anatsui, Deininger’s use of found materials, particularly in pieces like Womb II. which repurposes a red-stained cloth, demonstrates the ability of African artists to imbue objects with new cultural and symbolic significance. Both artists focus on the regenerative potential of these materials, reflecting themes of transformation and continuity.

The South African artist Nandipha Mntambo uses cowhide in her sculptures to address the tension between materiality, gender, and identity. Similarly, Deininger’s use of Kanga cloth, cowry shells, and crochet suggests an exploration of femininity and the role of women in maintaining cultural traditions, while also examining the friction between tradition and modernity.

One of the most prominent features in Deininger’s work is the repeated use of masks, a central symbol in African art, often used in rituals to communicate with ancestral spirits or to signify cultural archetypes. Deininger’s masks, however, take on a more layered significance, representing the fragmented or "negative" spaces left by colonial erasure. In this, her work recalls the practice of Ben Enwonwu, a Nigerian modernist who used masks to explore the intersection of tradition and modernity in post-colonial Africa. Deininger’s masks are not limited to representing tradition but engage with the complexities of identity in a globalized, post-colonial world. This places her work alongside artists like Wangechi Mutu, whose fragmented figures similarly critique the hybrid identities imposed on African bodies through colonialism, global capitalism, and migration.

The cowry shell, a recurring motif in Deininger’s work, carries profound cultural significance, symbolizing fertility, wealth, and spiritual protection across African societies. By incorporating cowry shells into her pieces, Deininger aligns her art with traditional African practices while also reflecting on the commodification of these cultural symbols through colonialism. The cowry shell also resonates with Simone Leigh, an African American artist who often uses these shells in her ceramic works to explore Black female identity and spiritual resilience.

Kanga cloth, which features prominently in Deininger’s installation work, is not just a fabric but a form of social communication in East Africa, often carrying Swahili proverbs and political messages. In this, Deininger’s work draws parallels with Faith Ringgold, who uses quilts as narrative devices in her exploration of African American history and identity. Both artists reclaim textile traditions as a means of resistance and storytelling, placing everyday objects in the realm of fine art to comment on political and social issues.

Louise Deininger

FIKIRA

ICH I Womb

ICH II Womb II

Negatives

Negatives II

PARO

Path

Shadow III

TAYA

The Portal

UMOJA

YATH Medicine

YOO